The Fake AI Copper Debate: Mispricing the Physical Layer

The market is trapped in a fake debate about copper versus fiber. The real bottleneck is long-lead power equipment, the macro grid, and a fracturing metal supply chain.

The market is stuck in a fake argument about the physical layer of AI.

If you listen to the current chatter around data center infrastructure, you are being fed a binary that doesn’t actually exist in the real world:

Myth #1: AI requires “hundreds of thousands of tons” of copper inside the data hall. The most‑shared extreme numbers are quite literally bad math—a game of telephone where “busbar copper per MW” got extrapolated into “whole-facility copper” and confused across kg/tons/pounds.

Myth #2: “Going all‑fiber” is a death sentence for copper. > The reality? You can’t model the physical constraints of an AI training cluster if you don’t understand the physics of how they are powered. Both of these myths miss the blindingly obvious: AI data centers are no longer just server farms. They are power plants.

Both of these myths completely miss the actual constraint. AI data centers are no longer just server farms. They are turning into power plants. The variables that actually dictate the buildout are power density, redundancy, and grid interconnection. It has nothing to do with what material is wrapped inside a fraction of the networking cables.

Disclaimer: This is not investment advice. It’s an analytical framework

+ a public-market watchlist for understanding how “robotics workloads”

could re-route compute spend across the stack. Do your own work /

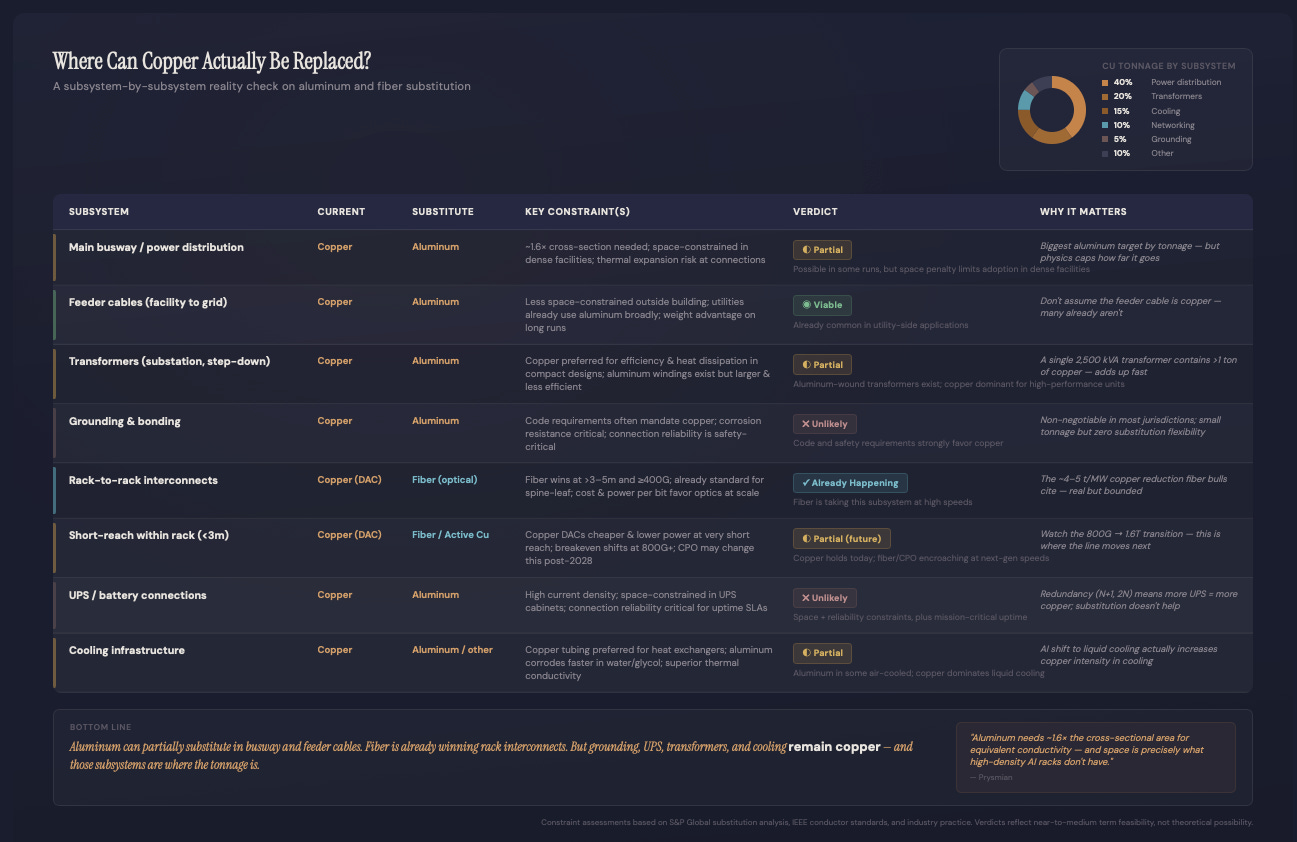

consult a licensed professional before acting.And for skeptics: the real bear case for copper isn’t fiber. It’s aluminum substitution in busway / conductors. But that threat is capped by physics: aluminum needs more cross‑section (space) for the same conductivity, and space is precisely what high‑density racks don’t have.

The “200 tons” story is a category error (and why it got misread)

The viral narrative about copper tonnage is a masterclass in what happens when financial analysts try to read engineering manuals.

Here is the actual context. NVIDIA published a technical post explaining why next-generation AI data centers must shift to high-voltage power architectures. To prove their point, they looked at legacy 54-volt systems. Because lower voltage requires massive amounts of physical metal to safely carry high power, pushing one megawatt of compute through a legacy rack requires roughly 200 kilograms of solid copper busbars. A busbar is simply the thick metal strip that conducts electricity inside the cabinet.

NVIDIA’s 800V/HVDC post put a real number on a very specific subsystem:

In a legacy 54V architecture, a 1 MW rack can require ~200 kg of copper busbar.

Scale that busbar-only subsystem to a 1 GW buildout and you get ~200,000 kg (200 metric tons) of copper for rack busbars. (NVIDIA Developer)

That number then got misinterpreted in both directions:

Some people (wrongly) treated 200 tons as the whole facility.

Others ran with an early, obviously wrong “hundreds of thousands of tons” framing which got publicly challenged and then stabilized into the correct interpretation (busbars, not the entire campus).

The key takeaway:

The “200 tons” number is useful, but only as a warning shot about low-voltage distribution hitting a wall and not as a way to model total copper demand.

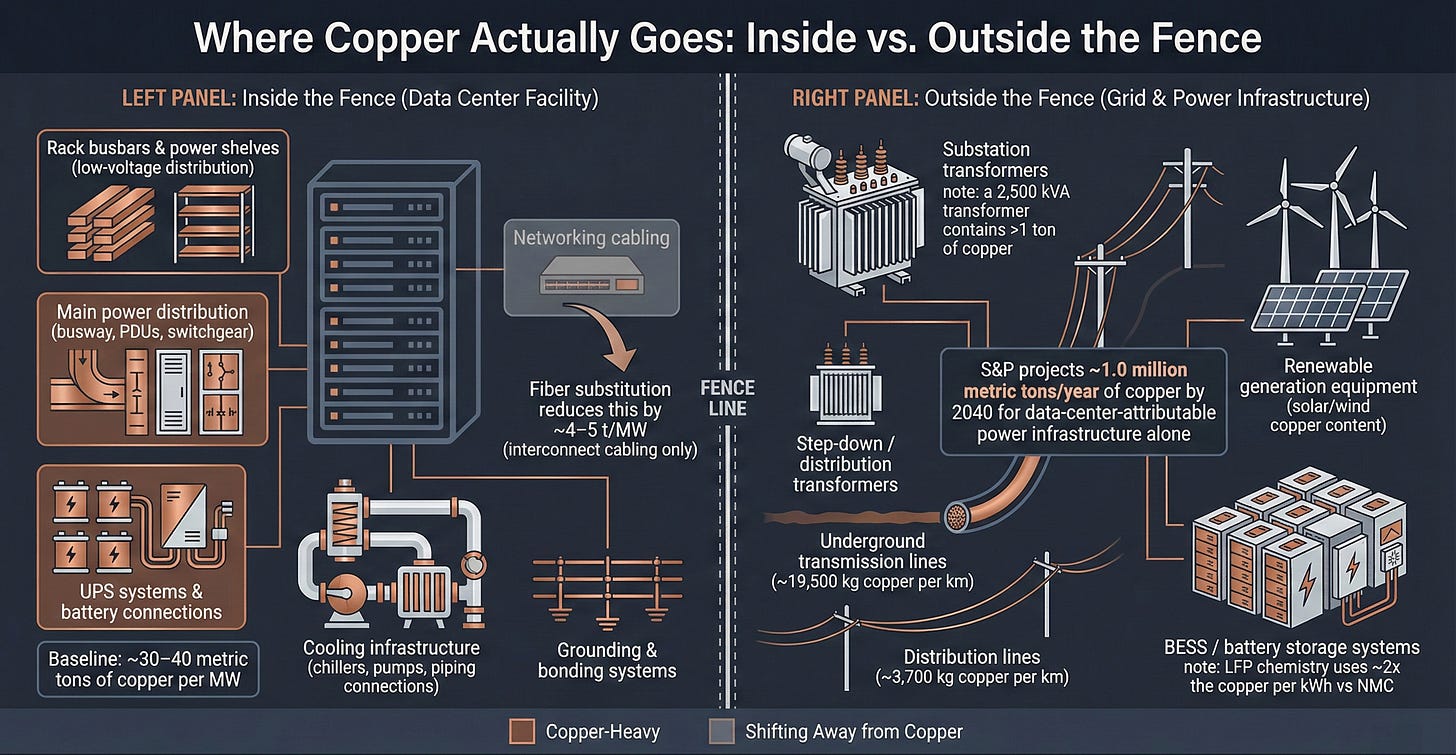

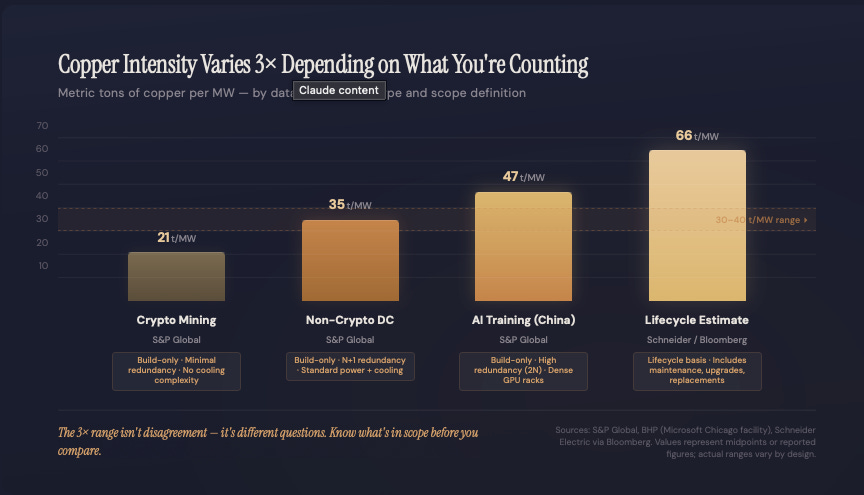

The number that matters: ~30–40 tons of copper per MW is the floor

If you want a modeling input that actually works in the real world, you need to stop debating internal rack components. The only metric you should anchor on is facility-wide copper intensity per megawatt.

Right now, the cleanest framework comes from S&P Global. They baseline standard data centers at roughly 30 to 40 metric tons of copper for every megawatt of IT capacity. To be clear, that is a Day Zero construction metric. It strictly measures the initial build and entirely excludes the copper required for future lifecycle refits.

That baseline is not arbitrary. It is a structural floor dictated by the single most important variable that financial models chronically underweight.

Redundancy is the multiplier

Data centers are not like conventional factories. A factory can tolerate downtime; an AI training cluster cannot.

So builders don’t design for “N.” They design for N+1 / 2N everything:

transformers

switchgear

busway / cabling

UPS + generation

cooling backbones

Redundancy is the absolute multiplier Data centers are not factories. A factory can tolerate a few hours of downtime. A billion-dollar AI training cluster simply cannot.

Builders never design for a baseline capacity. They design for N plus one, or even double the capacity, across the entire site. That means duplicating the transformers, the switchgear, the heavy cabling, the backup generation, and the cooling backbones.

This is exactly why theoretical models fail. They calculate the bare minimum copper needed to run a facility and stop there. Real-world copper intensity is always drastically higher because redundancy forces you to buy the most copper-dense equipment on the campus twice.

Reality check: the range is wide, but the floor is sticky

When you look across the industry, the estimates for copper intensity land in the exact same zip code. The variance you see in the numbers comes down to three specific choices: redundancy, rack density, and whether the model measures just the initial build or the entire lifecycle.

Look at the actual deployments. A standard Microsoft facility in Chicago maps out to roughly 27 tons of copper per megawatt. High-redundancy AI training clusters in Asia push closer to 47 tons per megawatt. Meanwhile, stripped-down crypto mining sites drop down to 21 tons. If you start factoring in lifecycle refits and upgrades over time, those estimates can easily shoot past 60 tons.

Bottom line: if you’re underwriting AI data center copper demand, 30–40 t/MW is not aggressive. It’s the base case.

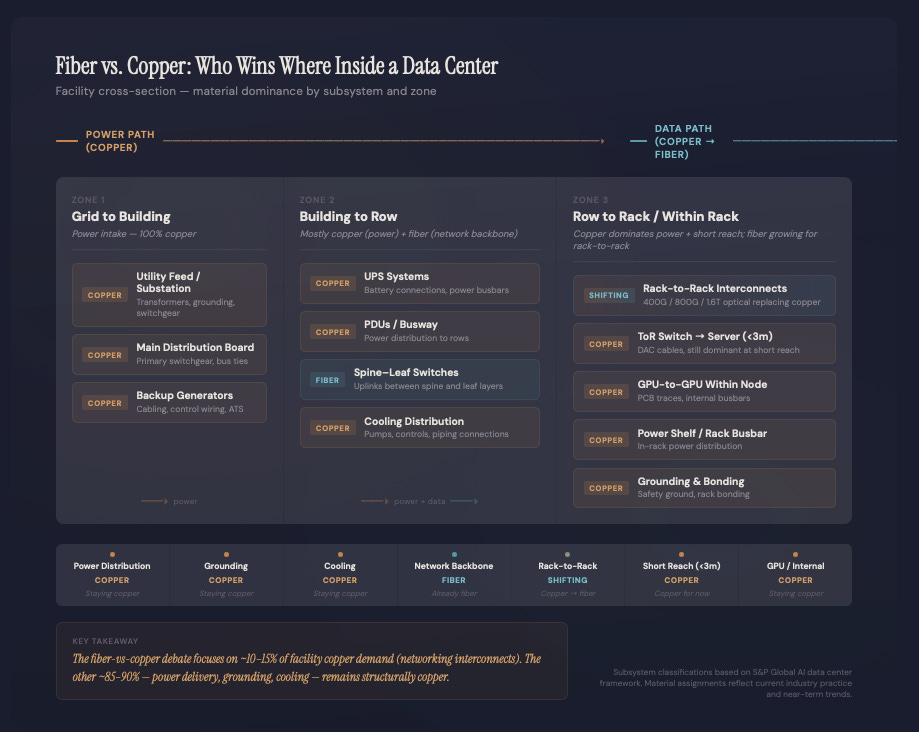

The “fiber delta” is real but it’s just not the main event

Here’s the cleanest way to frame the copper-vs-fiber question:

Fiber wins bandwidth. Copper carries amperage.

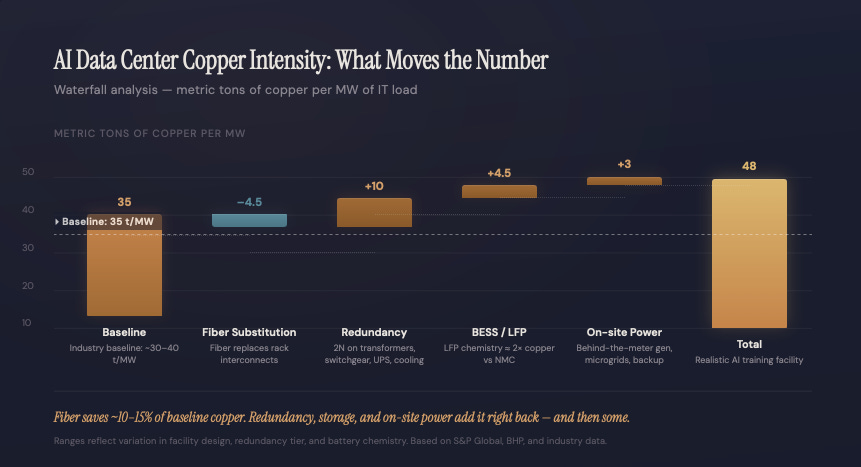

The one place copper actually loses inside the data hall is the interconnect cabling between racks. The industry is undeniably shifting toward fiber here. But you have to look at the actual magnitude. Going all-in on fiber reduces total copper intensity by roughly four to five tons per megawatt. Against a baseline of 30 to 40 tons, you are looking at a ten to fifteen percent haircut. That is a minor efficiency gain, not an extinction event.

The nuance here is that fiber only substitutes data interconnects. It does absolutely nothing to replace the heavy, amp-carrying copper in the power chain. Yes, fiber is taking market share, but it is taking share from a sliver of the buildout that does not move the needle. The structural driver of this entire trade is power delivery.

This is exactly what the market misunderstood about NVIDIA. Their warning was never that copper is disappearing. Their point was that legacy 54 volt power distribution physically breaks down as racks approach megawatt scale. That is why they are forcing the industry toward 800 volt direct current architectures. That viral busbar number was a symptom of the true underlying constraints in high-density computing. The bottlenecks are current, physical space, and heat.

NVIDIA’s point isn’t “copper will disappear”—it’s that 54V distribution hits physical limits as racks approach MW scale, which is why they’re pushing 800 VDC architectures for next‑gen “AI factories.” The busbar number is a symptom of the underlying constraint: current, space, and heat at extreme rack densities.

The hidden copper bull case is “outside the fence”

If you are looking for the true variant view in this trade, stop looking inside the data hall. The real edge is in the infrastructure that connects these hyperscale campuses to physical reality.

To model this correctly, you have to separate demand into two distinct buckets:

The copper consumed strictly inside the data center ecosystem.

The massive amount of copper required outside the facility to support it, specifically for power generation and grid expansion.

The critical nuance: Aluminum feeds the site, but the substation is copper

Because AI campuses require massive high-voltage interconnects, the immediate transmission lines often skew heavily toward aluminum. Utilities use aluminum conductors broadly across long distances to save weight and cost.

This is exactly where amateur models overclaim copper demand. If you want an accurate framework, use these two rules:

Never assume the incoming high-voltage feeder cable is copper.

Always assume the substation, the step-down transformers, the grounding grid, and the entire heavy equipment stack are massively copper-intensive.

S&P puts hard numbers on where copper shows up in the grid stack:

“Typical underground transmission lines” can use ~19,500 kg copper per km (and distribution ~3,700 kg/km) — depending on design. (S&P Global)

A 2,500 kVA transformer can contain >1 metric ton of copper, ~30% of its mass. (S&P Global)

The number that should change your model

When you aggregate the power infrastructure required to support these data centers, the forecast hits one million metric tons of copper per year by 2040. That volume splits cleanly down the middle: half a million tons for new renewable generation, and half a million tons for transmission and distribution. Specifically heavy underground lines.

This is your outside the fence alpha. Even if the data hall itself becomes hyperefficient and replaces internal cables with fiber, the mandatory grid expansion acts as a massive, parallel call on copper.

On-site power isn’t just a grid workaround. It’s a copper multiplier

The old model was simple: build a facility and plug it into the grid. The new model for AI factories is entirely different. Because interconnection queues are stretching into the next decade, builders are pivoting to a "bring your own stability" mindset. The builder behavior is shifting from “plug into the grid” to “bring your own stability”:

behind-the-meter generation

diesel backup at scale

microgrids

BESS layered on UPS

Grid operators are now explicitly designing rule sets that encourage large loads to bring capacity. For example, Reuters describes PJM proposals that include “bring‑your‑own‑generation” style options and “connect‑and‑manage” frameworks to accommodate the data‑center load wave.

Here is the realization that breaks most models. When an operator goes off-grid or builds behind the meter to bypass utility bottlenecks, they do not escape the copper thesis. They actually double down on it. You are effectively forcing a software company to build a local power plant. Furthermore, because megawatt-class racks create violent electrical transients, operators have to install entirely new hardware layers like supercapacitors and battery banks just to condition the power and keep the GPUs from crashing. Bypassing the grid does not kill copper demand. It multiplies it.

The LFP turbocharger (the part most models miss)

Stationary storage is converging on LFP for safety and cost. And copper intensity varies materially by chemistry.

As the entire stationary storage industry is rapidly converging on Lithium Iron Phosphate, or LFP, for its superior safety and cost profile. But here is the physical reality of battery chemistry. LFP cells require nearly double the copper intensity per kilowatt-hour compared to traditional high-energy cells.

This matters because it means:

A data center adding “just” hundreds of MWh of backup/peak-shaving can add hundreds of tonnes of copper demand quickly, and

The chemistry mix can swing that number meaningfully.

This is the hidden multiplier. Because LFP has a lower energy density, you need significantly more physical cells to reach your target capacity. Longer duration storage requires more cells, which means a massive increase in copper anode foil, internal busbars, and heavy system cabling.

When an AI data center adds just a few hundred megawatt-hours of battery backup for peak shaving or stability, it instantly creates demand for hundreds of metric tons of new copper. The math here is undeniable. The few tons of copper you save by switching to fiber optics are entirely real. But the battery energy storage system in the parking lot eats those savings alive.

Net: fiber savings are real, but BESS can eat the savings.

The first crunch is equipment, not metal

If you want the operational constraint that shows up before commodity tonnage does, it’s this: long‑lead power equipment.

Reuters reporting highlights how grid equipment shortages are already structural. For example, generation step‑up transformer delivery times averaged ~143 weeks in Q2 2025, and the industry has been responding with major factory investments because demand (renewables + data centers + electrification) is outrunning capacity.

This matters for investors because it changes the “copper trade” from a pure commodity view to an embedded‑copper capex bottleneck view: transformers, switchgear, and HV gear can gate commissioning even if copper cathode is available. Separate Reuters coverage also points to transformer supply shortfalls as demand surges.

Translation: the risk isn’t “running out of copper wire.” The risk is waiting on copper‑intensive hardware while GPUs depreciate in a warehouse.

The Sovereign Supply Shock: Copper is now a national security asset

Stop looking at the 2040 macro forecasts. The physical copper market is already breaking down today. The market assumes supply deficits are a distant, corporate problem. The reality is that the geopolitical supply chain fractured in early 2026, and governments are now actively panicking.

The smelting engine is starving

Consensus assumes China has an unbreakable monopoly on processing. The truth is much worse: they overbuilt their smelting capacity so aggressively that they literally ran out of rock.

Global mine supply cannot feed the furnaces. We have officially entered the “zero processing fee era.” Because raw ore is so scarce, the treatment and refining charges (TC/RCs) that smelters rely on have completely collapsed into negative territory. Smelters are now effectively paying to process rock. The bleeding got so bad that China’s top smelters were forced into an emergency pact to slash their primary production capacity by over 10% in 2026. The bottleneck is no longer a Chinese monopoly. It is a global engine starving for raw material.

The sovereign scramble

Western governments have realized the math is broken. In late 2025, the United States officially added copper to the USGS Critical Minerals List. But they aren’t just writing policy—they are deploying capital.

The US government is now backing billion-dollar investment vehicles to actively bypass open markets and buy direct stakes in mega-mines across the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia. Copper is no longer trading purely on corporate demand. It is trading as a sovereign security asset.

The foundation is cracking While nations scramble to secure new rock, the legacy foundation is decaying. Massive, aging mega-mines in Chile and Indonesia are fighting viciously depleting ore grades. Operators are pouring billions of dollars into capital expenditures just to watch their total output fall.

When you combine a starving Chinese smelting sector, aggressive US sovereign stockpiling, and collapsing legacy mine output, the supply deficit is not a 2040 model projection. It is a 2026 reality.

Supply: why this can actually become a crunch (and why price is the clearing mechanism)

If the AI buildout were the only demand shock, the copper market might survive. The problem is that AI is colliding directly with a global grid that is already tapped out by broader electrification.

The baseline math on the supply side is a structural gut punch:

Global copper demand is scaling from 28 million metric tons today to roughly 42 million metric tons by 2040.

Without an unprecedented expansion in mining, we are staring down a massive shortfall of 10 million metric tons over that same timeframe.

Primary mined supply is explicitly set to peak around 2030.

New discoveries are structurally paralyzed. Taking a mine from discovery to production takes well over a decade, suffocated by permitting, litigation, and environmental opposition.

Furthermore, the supply chain is not just geologically constrained. It is geopolitically bottlenecked. Just six countries control two-thirds of global mining production. The processing layer is even more vulnerable, with China holding forty percent of global smelting capacity and absorbing two-thirds of all mined concentrate imports.

What the crunch actually looks like in practice

When the market breaks, it will fracture along two distinct fault lines:

The Commodity Crunch: Physical market tightness in raw cathodes, concentrates, and scrap.

The Equipment Crunch: Severe bottlenecks in copper-heavy hardware like transformers, switchgear, and heavy busways.

In the AI era, the equipment bottleneck hits first. Copper is not just a raw input. It is the core ingredient embedded in the long-lead electrical hardware that dictates whether a facility can actually turn on. You can secure all the GPUs in the world, but if you are stuck in a queue for a copper-dense transformer, your data center is just a very expensive warehouse.

The Capex Reality Check We need to stop treating copper as a negligible line item. Look at a standard 230-megawatt greenfield AI campus. Assuming a heavy-redundancy baseline of 44 tons per megawatt, that single facility requires 10,000 tons of copper.

With copper decisively pushing past $11,500 per ton in late 2025, you are looking at over $115 million in raw copper costs for a single $3 billion data center. When you try to force a fast-twitch AI demand shock through a slow-twitch, highly concentrated mining supply chain, there is only one way the market clears. The price has to go up.

So will price go up?

No one can predict a near-term price target from a single piece of research, but the structural math is undefeated.

The market is facing an immediate, fast-twitch demand shock from AI data centers and global power grids. It is colliding with a slow-twitch supply chain constrained by 17-year mine development timelines and heavily bottlenecked processing infrastructure.

You cannot force an immediate, generational demand shock through a geologically fixed supply limit without breaking something. There is no magic technological fix for a physical shortage. Price is the only variable left to clear the board.

The real bear case: aluminum substitution (and why it’s bounded)

If copper gets expensive enough, the industry engineers around it. That’s always true.

But here’s the nuance that matters for AI data centers:

Aluminum is cheaper and lighter, but it has lower conductivity, so you need ~1.6× the cross-sectional area for the same performance.

Utilities often use aluminum conductors, especially where space/weight economics dominate.

Inside data centers, S&P notes copper is preferred over aluminum for power distribution because data centers are space-constrained and have elevated fire/heat considerations.

Aluminum substitution runs into space and heat dissipation barriers.

Even where aluminum is technically feasible, connectors/termination practices, heat rise, and real estate in dense busway runs become the practical constraints especially in high‑density halls.

The right conclusion isn’t “aluminum can’t happen.”

It’s: aluminum can cap the upside in certain subsystems (busway), but it doesn’t break the thesis because the MW buildout (and the copper fortress outside the fence) is still marching forward.

The Optics Trade: Fiber wins the volume game

Now the second half of the trade: optics.

The optical paradox

When you look at fiber substitution through the lens of a copper model, it looks like a minor headwind where you shave roughly four to five tons of metal off the per-megawatt baseline. But when you look at it through the lens of an optics model, the math goes completely parabolic.

The sheer volume of high-speed optical links inside an AI factory does not scale linearly. It scales exponentially across four distinct vectors:

GPU count

cluster size

east–west bandwidth per GPU

network topology complexity

This creates a dynamic where both sides of the trade can be wildly bullish at the exact same time. If you take only one thing away from this structural shift, it is this:

Copper is the tonnage story (power infrastructure).

Optics is the volume story (links and upgrades).

Copper is mostly Day‑0 CapEx; optics behaves more like recurring spend

This is the nuance investors miss.

Copper gets installed once (or at least infrequently) as part of facility capex.

Optics gets refreshed as link speeds step up — and that cadence is accelerating.

LightCounting expects massive deployments of 800G transceivers in 2025–2026, with 1.6T and 3.2T “soon after.”

Coherent’s market view similarly frames a rapid shift toward 800G+ and beyond this cycle.

So a “more optical” data center isn’t just a one-time capex shift — it’s a faster upgrade loop across the photonics supply chain.

CPO timing: inevitable, but not instantaneous

Co-packaged optics (CPO) is the logical endgame for power/thermal efficiency at extreme bandwidth, but timelines matter.

Reuters reported Jensen Huang saying NVIDIA will use co-packaged optics in networking switch chips through 2026, but that it’s not reliable enough yet for flagship GPUs, with mass adoption potentially 2028+. (Reuters)

That matches the practical deployment path most builders see:

Today: copper dominates ultra-short reach; fiber dominates rack-to-rack / row-to-row at high speeds

Mid term: more optics density (more 800G/1.6T), plus active copper where it still makes sense

Later: CPO spreads as reliability and manufacturing mature — pulling more of the optics value chain into packaging/assembly rather than pluggable modules

CPO isn’t for “adjacent cabinets” — it’s for switch power/thermal at extreme radix

A common pushback (often seen on social media) is: “Why would you need CPO just to connect adjacent cabinets—use copper.” That’s directionally right for very short reach.

But CPO’s economic target isn’t “one short cable.” It’s the power/thermal cost of pluggables and long electrical paths once you’re pushing 800G→1.6T class bandwidth across high‑radix switches and large fabrics. That’s why NVIDIA’s public messaging has been: switch chips first (through 2026), GPUs later, with broader adoption potentially 2028+ as reliability/manufacturing mature.

Net: Copper remains the rational choice where geometry makes reach trivial; CPO shows up where power per bit and density dominate.

The CPU comeback: agentic workloads pull CPUs (and networking) back into the frame

The most underpriced second order effect in the “AI factories” narrative may be CPU demand inside the stack, we have already made a dedicated article on this but since then NVIDIA and Meta just made this explicit with a multiyear deal that includes not only GPUs (Blackwell/Rubin) but also NVIDIA Grace and future Vera CPUs, with Grace positioned for broader data processing tasks and AI‑agent style workloads.

If CPU cycles become the limiter for certain inference/agentic pipelines (data prep, retrieval, orchestration, safety layers), it strengthens the case for tunable CPU:GPU ratios over time i.e., potential CPU disaggregation rather than permanently “fixed” GPU‑centric rack designs.

The actual “so what” (for builders and investors)

If you’re building neocloud / AI campuses

The risk is not “running out of copper wire.”

The risk is getting stuck in the queue for copper-heavy power hardware and grid interconnect approvals

If you do not secure your transformers and switchgear early, your GPUs will simply depreciate in a dark warehouse. Power access is the actual product you are building.

If you’re modeling copper demand

Delete the "200 tons per gigawatt" facility assumption from your spreadsheet immediately. It is a fundamental misread of a busbar subsystem. Your baseline must start at 30 to 40 tons of copper per megawatt of IT capacity for the inside-the-fence build. If you assume aggressive fiber substitution, shave four to five tons off that number. Then, aggressively model the outside-the-fence allocation. The grid and power generation infrastructure required to support these sites acts as a massive, parallel copper multiplier.

If you’re modeling optics demand

Stop worrying about copper substitution. Optics demand does not grow because copper dies. Optics demand explodes because the sheer volume of physical links multiplies exponentially alongside GPU cluster sizes, spine-leaf network complexity, and the relentless upgrade cadence from 800G to 1.6T and beyond.