NVIDIA’s Christmas Eve Gift: Groq and the New Physics of Inference

How splitting the supply chain unlocks the next decade of reasoning models, brownfield capacity, Supply-Chain Physics, and token economics.

1. Executive Summary: The Christmas Eve Paradigm Shift

On December 24, 2025, NVIDIA struck what reads like a licensing deal—but behaves like an acquisition. Groq announced a “non‑exclusive” license of its inference chip technology to NVIDIA, while Groq founder Jonathan Ross and key Groq executives/engineers move to NVIDIA; Groq’s cloud business continues operating and Groq stays “independent” under a new CEO.

If you strip away the legal wrapper, the strategic message is blunt:

NVIDIA is conceding—in public—that training and inference have bifurcated so hard that one architecture cannot economically dominate both. The GPU remains the throughput king for training. But the next margin pool is inference (tokens), and inference is being reshaped by (1) reasoning/System‑2 models that “think” longer at test time and (2) supply chain physics—HBM + CoWoS are becoming a tollbooth on how fast the world can scale GPU supply.

This report is designed to be an example on how you can leverage the FPX “Bottlenecks Beyond Power” framework to understand movements in the market such as this one better :

Part 1 (Memory) explains why HBM + CoWoS is the hard governor on GPU scaling (the Memory Wall + packaging bottleneck).

Part 2 (Networking) explains why the next bottleneck becomes connectivity (copper → optics → CPO) as “AI factories” scale.

This report explains how the NVIDIA↔Groq move changes what gets built next (and therefore who wins in memory, optics, networking, power, and “capacity as a product”).

In the Paid section we break down the supply chain implications and what this really means not only for the Memory and Networking players in the space but also how you can refine your strategy if you are a Colocation Operator, buying or selling Powered Land or are an Investor in the space.

The core thesis

Groq isn’t valuable because it was about to “kill NVIDIA.” Groq is valuable because it is an orthogonal path to inference capacity:

HBM‑less, SRAM‑centric inference silicon (reduces dependence on the most constrained layer of the GPU supply chain).

Compiler‑scheduled determinism (reduces tail latency/jitter—crucial for agentic and reasoning workflows).

A second manufacturing lane (GlobalFoundries now; Samsung 4nm next-gen planned) that can ramp without waiting for CoWoS slots. (Groq)

In other words:

NVIDIA didn’t buy “a chip.” NVIDIA bought a second factory door that doesn’t pass through the CoWoS/HBM tollbooth.

And the second‑order consequence is the real story: once NVIDIA has two doors, it can segment customers, price discriminate, and keep control of the inference annuity—even as hyperscalers push harder to escape CUDA.

2. The Strategic Context: Why ~$20B? Why Now?

The reported ~$20B figure (a ~3x premium to Groq’s last $6.9B September 2025 valuation) underscores that this is not a revenue multiple story. It is a Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) story.

2.1 The transition from Training to Inference is a transition from CapEx to COGS

A clean way to frame the macro shift:

Training is CapEx: build the model once (or periodically).

Inference becomes COGS: every user query, agent loop, tool call, and “reasoning” step is a recurring cost line item.

As AI products become “always on,” CFOs stop asking “How fast can we train?” and start asking “What is our cost per useful token delivered?”

That is why NVIDIA’s inference posture matters more now than in 2021–2023. This is the phase where unit economics become strategy.

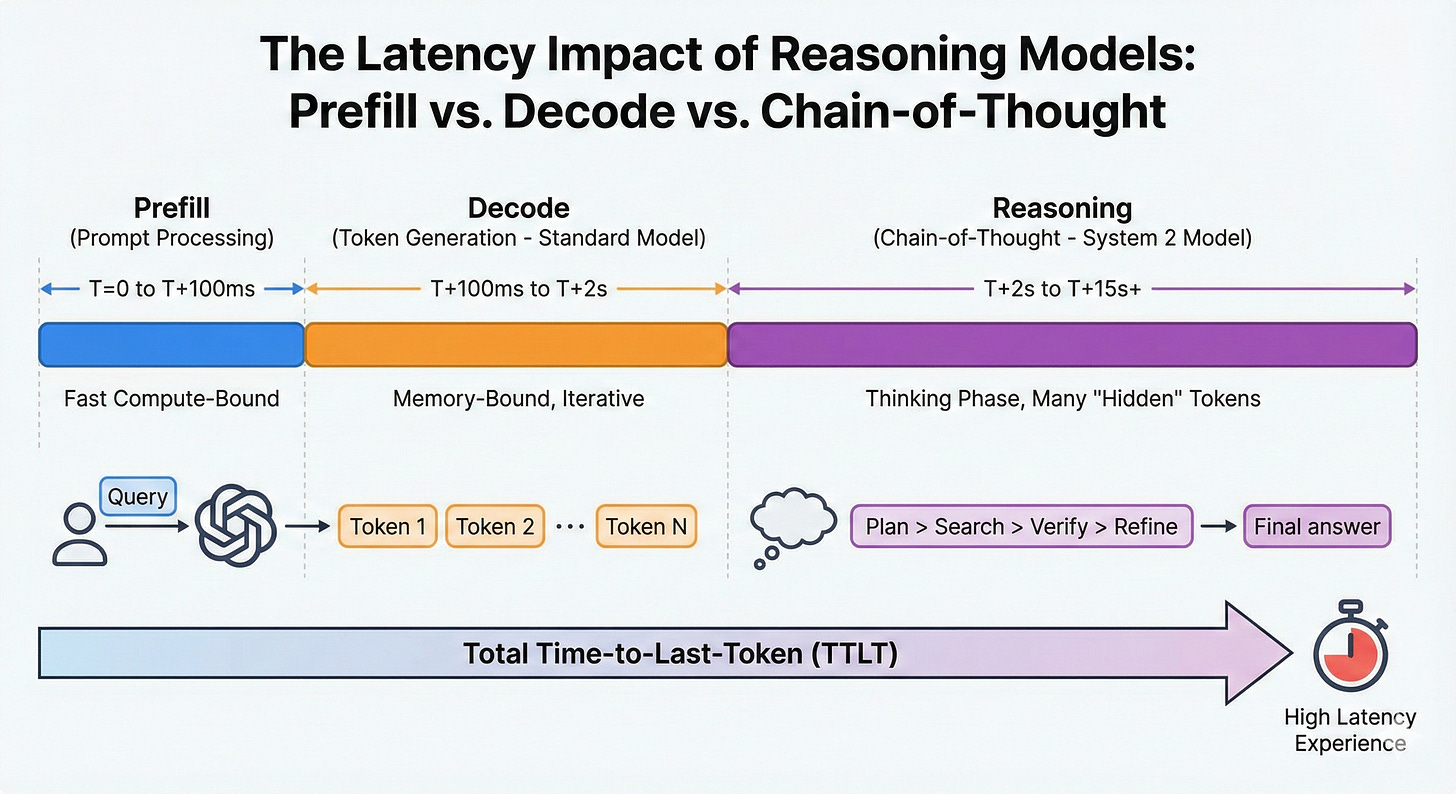

2.2 The real “Why Now?” is the DeepSeek / o1 factor: reasoning models are token multipliers

The industry hype cycle moved from “chat” to “reasoning.”

OpenAI’s o1 series popularized the idea that models spend more time thinking before responding, scaling performance with test‑time compute. (OpenAI)

OpenAI’s own developer docs are explicit that reasoning models “think before they answer” and can consume substantial “reasoning tokens” as part of producing a response.

DeepSeek’s R1 paper directly characterizes o1‑style reasoning as “inference‑time scaling” by increasing Chain‑of‑Thought length.

What that means in infrastructure terms:

Reasoning models don’t just generate the visible answer tokens. They generate large internal token sequences (reasoning tokens / thought tokens), which pushes you into a world where Time‑to‑Last‑Token (TTLT) becomes the user experience bottleneck, not just Time‑to‑First‑Token.

Strategic insight: NVIDIA didn’t just “buy inference.”

NVIDIA bought a path to make System‑2 reasoning feel like System‑1 latency.

If Groq collapses the “thinking loop” latency enough, it doesn’t reduce compute spend. It creates demand (Jevons paradox): cheaper inference becomes more inference, more agents, more loops, more tool use, more tokens.

2.3 The hyperscaler threat is no longer “chips.” It’s “escape velocity.”

Google is the cleanest case study. It has:

Custom silicon explicitly positioned for inference (e.g., TPU “Ironwood” described as designed for the “age of inference”). (blog.google)

A push to expand TPUs beyond internal use: As FPX first reported in September, Google has moved to sell TPUs directly into customer data centers, not just via Google Cloud—marking a strategic escalation from internal acceleration to full-stack infrastructure competition.

A direct attack on NVIDIA’s software moat: As FPX reported earlier this year, Google launched TorchTPU to make TPUs first-class PyTorch targets—explicitly reducing CUDA switching costs and partnering with Meta to accelerate ecosystem adoption.

This is exactly the “build vs buy” shift that shrinks NVIDIA’s default TAM if left unaddressed.

2.4 NVIDIA isn’t mainly playing defense against Groq. It’s playing offense with Groq.

Groq alone had a scaling problem: not physics, but distribution.

Inference hardware doesn’t win by being clever; it wins by being easy to buy, easy to deploy, and easy to program. NVIDIA already owns those channels: the software stack, the OEM/ODM ecosystem, the cluster networking narrative, and the default developer workflow.

So the offensive version of this deal is:

Groq brings a new inference architecture + second supply chain lane.

NVIDIA wraps it in the world’s dominant AI software ecosystem and global go‑to‑market.

That combination is more dangerous than Groq as an independent upstart.

3. Architectural Deep Dive: The Physics of the LPU vs. GPU

This deal only makes sense if you treat it as buying a different execution philosophy. Determinism is the new requirement for agentic workflows.

3.1 Determinism: why “compiler-first” matters more than raw TOPS

GPUs are dynamically scheduled machines. That’s great for variable workloads. But inference graphs—especially serving fixed model architectures—are known ahead of time.

Groq positions its architecture around deterministic execution and compiler scheduling, explicitly reducing the need for complex runtime scheduling and enabling tightly controlled data movement and timing.

Why that matters now (Agentic AI): the Straggler Effect becomes the tax.

In a multi-agent workflow (planner, executor, retriever, verifier, tool‑caller), your end‑to‑end latency is limited by the slowest sub‑call. If one “agent” stalls, the orchestration graph stalls.

Determinism isn’t just “faster.” It’s synchronization. It’s predictable TTLT. That’s an infrastructure primitive for agent swarms.

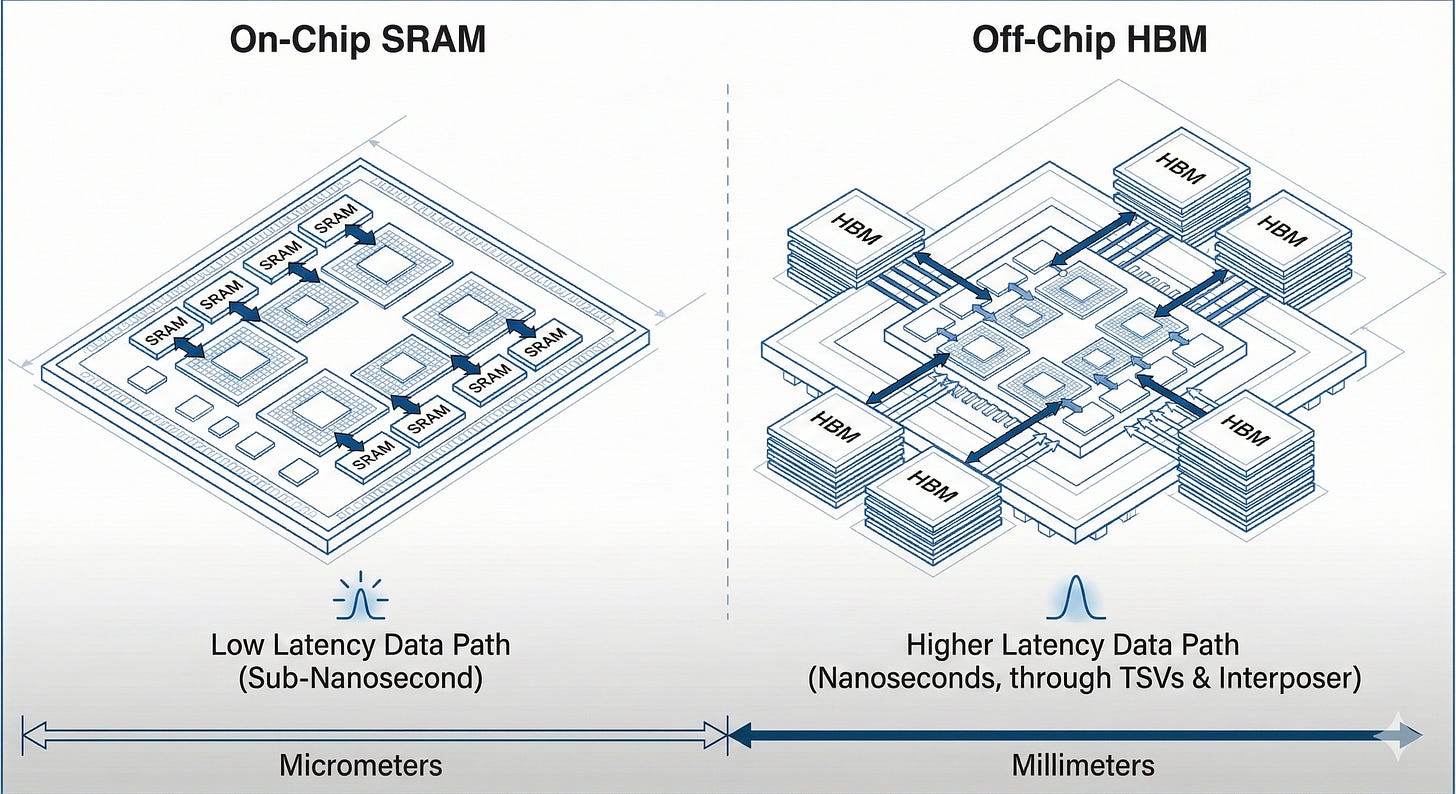

3.2 SRAM vs. HBM: Groq is a bet on breaking the Memory Wall by changing the memory hierarchy

In Part 1, we framed HBM as the “cutting board”: incredibly fast, physically close to the compute, but scarce and packaging‑constrained. (research.fpx.world)

Groq was among the upstarts that do not use external high‑bandwidth memory chips, instead relying on on‑chip SRAM—which speeds interactions but limits the model size that can be served.

Groq’s own materials emphasize “massive on‑chip memory” and a software-first approach that makes the hardware behave predictably.

Translation: Groq is “HBM-negative” per accelerator.

But it can be “network-positive” in the aggregate, because sharding and chip-to-chip fabric become central as models scale.

3.3 The elephant in the room: Cerebras is the “SRAM physics” competitor this deal validates

Cerebras is one of the primary rivals in the SRAM-centric, HBM‑less inference approach.

Cerebras’ wafer-scale pitch is even more explicit: the WSE‑3 announcement highlights 44GB of on-chip SRAM and extreme memory bandwidth—essentially turning “SRAM first” into an entire wafer-scale system design.

The “Validation Trap”:

This deal is a market-level validation of the SRAM-over-HBM inference thesis. But it also collapses the narrative: the alternative physics is no longer an alternative to NVIDIA—it is now being absorbed into NVIDIA’s orbit.

For competitors, that’s brutal. They can be right on architecture and still lose on ecosystem.

3.4 Networking: Groq’s determinism is a networking strategy, not just a compute strategy

Part 2 made the point that the network is the “nervous system,” not a sideshow. (research.fpx.world)

Groq’s scaling story inherently relies on chip-to-chip connectivity. Public reporting on Groq’s systems describes LPU racks stitched together with fast interconnect, including fiber-optic links in some scaling narratives. (OpenAI Platform)

Meanwhile NVIDIA is already driving deeper optical integration (CPO) and explicitly pulling major photonics suppliers into its ecosystem (as we covered in Part 2). (research.fpx.world)

Second-order implication:

If inference becomes cheaper and more distributed (more sites, more “inference hubs”), you get:

More front-end network + DCI optics (more regions, more replication, more east-west).

A faster push toward CPO and integrated optics inside large AI fabrics (power + density pressure).

This is why the “Groq + NVIDIA networking” combination is strategically meaningful. Groq’s deterministic execution model is a natural fit for future fabrics that behave more like a “virtual wafer” (your Google piece calls this out explicitly as well). (research.fpx.world)

3.5 Prefill vs Decode: the hybrid future is already visible in NVIDIA’s own roadmap

Here’s the key missing link that makes your “Speculative Decoding card” thesis feel inevitable:

NVIDIA itself is increasingly describing inference as two different workloads:

Context/Prefill (compute-intensive)

Decode/Generation (memory-bound)

This “disaggregated serving” framing shows up in reporting on NVIDIA’s recent disclosures, including the idea that splitting prefill and decode across different GPU pools can increase throughput.

And the roadmap implication is explicit: “Rubin CPX” is discussed as designed for “massive-context inference,” paired with full Rubin GPUs for generation.

This is the opening for Groq.

If decode is the memory/jitter bottleneck and Groq is an HBM‑less, deterministic decode engine, then Groq technology can become the “decode organ” inside a broader NVIDIA inference system—even if it never ships as a standalone Groq-branded product.

4. Manufacturing and Supply Chain: The “Second Source” Strategy

This is the most underappreciated strategic payload in the entire deal.

4.1 The CoWoS + HBM bottleneck is still the governor for GPU supply

In Part 1, we laid out why HBM is scarce and why GPU delivery schedules are gated by HBM stacks, CoWoS-class advanced packaging, and substrate constraints—not just wafers. (research.fpx.world)

If inference growth continues to be served primarily by HBM-rich GPUs, then inference expansion inherits the same bottlenecks as training.

4.2 Groq opens a second lane: inference capacity that is structurally less dependent on HBM and CoWoS

Groq’s approach avoids external HBM by using SRAM on-chip. Groq’s own funding release states it planned to deploy 108,000 LPUs manufactured by GlobalFoundries by end of Q1 2025—showing a concrete deployment plan outside the “TSMC CoWoS + HBM” lane. (Groq)

Most surces close to Groq heard directly from them that Groq contracted Samsung Foundry to manufacture next-gen 4nm LPUs.

That’s the orthogonal supply chain in one sentence: more inference capacity without consuming more CoWoS slots.

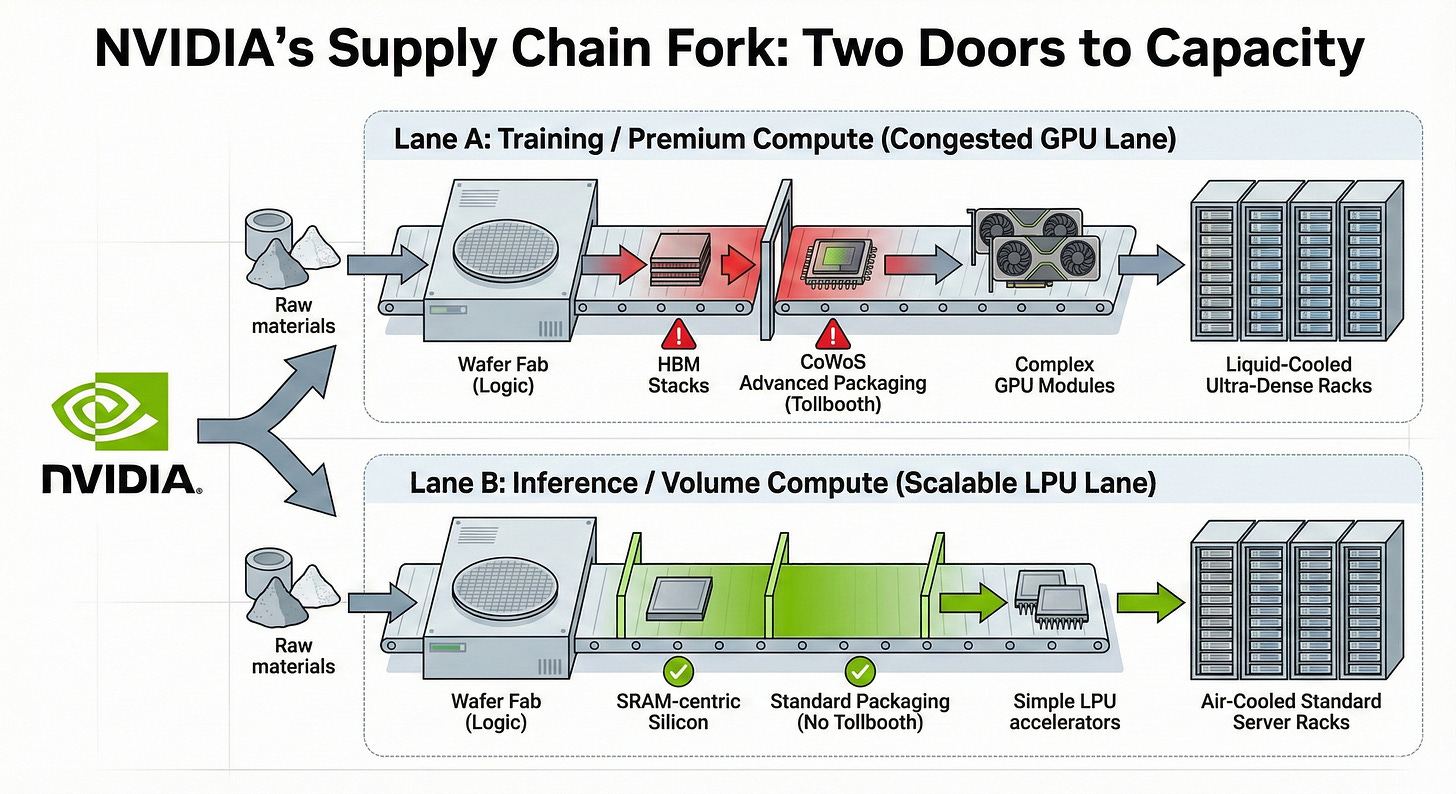

4.3 The visual mental model: NVIDIA just opened a second factory door

If you’re building a “physics-first” infrastructure map, draw this fork:

(CONSTRAINED LANE)

TSMC CoWoS + HBM stacks → GPU (training + some inference) → ultra-dense racks

|

| (UNLOCKED / MORE COMMODITY LANE)

└→ SRAM-centric inference silicon (HBM-less) → standard packaging → inference pods

Or even more simply:

Red lane (congested): HBM → CoWoS → GPUs → training factories

Green lane (flowing): SRAM → standard packaging → inference engines

“NVIDIA has effectively opened a second factory door that doesn’t lead through the CoWoS tollbooth.”

4.4 Second-order infrastructure effects of this supply chain fork

If NVIDIA can serve more inference demand through a less constrained lane:

HBM stays scarce—but the incremental HBM-per-inference-dollar ratio falls.

TSMC CoWoS capacity can be prioritized for the highest-margin training systems (and premium inference SKUs that still need HBM).

Inference deployments can fragment geographically (more colo, more enterprise, more sovereign deployments), because you’re no longer waiting on the most constrained packaging supply chain to ship boxes.

That last point is where Part 2 and Part 1 intersect: fragmentation increases optics/DCI and “deployable power” demand even if single-rack density is lower.

5. Economic Implications: The Tokenomics of 2026

5.1 The “Option A / Option B / Option C” segmentation becomes NVIDIA’s pricing weapon

Your framing is right, and this deal supercharges it:

Option A: NVIDIA GPUs (premium training + premium inference)

Option B: NVIDIA‑owned inference alternative (Groq-derived)

Option C: build from scratch (hyperscaler ASIC program)

The real power is that NVIDIA can now price discriminate across inference segments:

High-margin, “must-have” customers stay on the GPU stack.

Price-sensitive, latency-sensitive inference gets routed to an NVIDIA inference line that competes directly with hyperscaler ASIC economics—without forcing customers to leave the NVIDIA ecosystem.

This is a defensive moat against the Hyperscaler internal silicon. NVIDIA can now say: “Why build your own TPU when our 'Option B' is cheaper, faster, and already runs your software?”

This isn’t just revenue capture. It’s switching-cost engineering.

5.2 The Chain-of-Thought multiplier: why this is an inference deal, not a chip deal

OpenAI says reasoning models “think before they answer,” producing a long internal chain of thought; and OpenAI’s docs treat “reasoning tokens” as a first-class part of the token budget. (OpenAI Platform)

DeepSeek explicitly frames o1 as “inference-time scaling” by lengthening Chain-of-Thought.

Infrastructure translation:

More reasoning tokens → more decode work → more TTLT pain → more value in deterministic, fast token generation.

This is why Groq’s architecture is suddenly “worth $20B” (if CNBC’s number is accurate). It is the first credible path to keep reasoning UX from feeling broken at scale.

Callout: The Jevons Paradox of Inference

If NVIDIA/Groq lowers the cost and latency of inference by 10×, we won’t spend less on compute.

We will run more reasoning loops, more tool calls, more multi-agent plans, and more retrieval.

Cheaper tokens create more tokens.

5.3 Memory market implications (Link back to Part 1)

HBM is still the premium profit pool, and training remains HBM-hungry. But this acquisition creates a medium-term question: does inference growth continue to monetize through HBM content?

Groq avoids external HBM via SRAM.

Part 1 explains why HBM supply is constrained and why CoWoS and substrates are the bottleneck.

Second-order view:

If inference shifts to HBM-less engines, HBM demand doesn’t collapse—it reallocates toward training and top-end GPUs.

But the slope of “HBM dollars per incremental inference dollar” could flatten over time. That’s the subtle risk.

5.4 Networking + optics implications (Link back to Part 2)

Groq-style inference scaling likely increases:

Endpoint count (more chips, more nodes, more sites).

Front-end bandwidth demand (more inference hubs, more DCI).

Pressure to reduce network power (which accelerates optics integration).

So the likely net is volume support for networking and optics, with a form-factor transition: a long-run migration from pluggables toward more integrated photonics in back-end fabrics (while DCI remains a separate growth vector).

6. Software Ecosystem: CUDA meets Compiler‑First Design

Groq’s problem was never performance.

It was where developers pay the switching cost.

Inference buyers do not want a new compiler, a new kernel language, or a new deployment workflow. They want endpoints, latency guarantees, and uptime. NVIDIA understands this—and that’s why the Groq deal is fundamentally a software play.

6.1 From CUDA Lock-In to Runtime Lock-In

CUDA was NVIDIA’s original moat, but inference changes the terrain. Most inference workloads in 2026 are:

containerized,

API-driven,

deployed via operators and orchestration layers.

That shifts lock-in away from kernels and toward the runtime.

NVIDIA’s move is to make NIM (Inference Microservices) the control plane for inference. Once a model is deployed as a NIM endpoint, the developer no longer targets a chip. They target a service contract.

At that point, hardware becomes an implementation detail.

6.2 Groq Becomes a Backend, Not a Platform

NVIDIA does not need to “port CUDA to Groq.”

It simply needs to hide Groq behind NIM.

Under this model:

the developer writes to the NIM API,

NVIDIA owns batching, scheduling, telemetry, and failover,

and the runtime dynamically selects the silicon.

GPU for training and memory-heavy prefill.

Groq-style engines for deterministic, low-jitter decode.

The user never “chooses Groq.”

They choose latency and cost profiles.

That is the strategic inversion.

6.3 Disaggregated Inference Becomes a Software Routing Problem

Inference is already bifurcating:

Prefill: memory-heavy, throughput-oriented.

Decode: latency-sensitive, jitter-sensitive, dominated by reasoning loops.

NVIDIA’s software stack is the natural place to broker that split.

Once this logic lives in NIM:

disaggregation becomes the default,

hardware specialization becomes invisible,

and performance gains accrue without ecosystem fragmentation.

Groq’s determinism is no longer an alternative worldview.

It becomes an internal acceleration mode.

6.4 The Real Strategic Outcome

This is how NVIDIA neutralizes alternatives without fighting them head-on.

Instead of competing with new programming models, NVIDIA:

absorbs the best architecture,

hides it behind the dominant runtime,

and turns “hardware choice” into a private scheduling decision.

The moat shifts upward:

from CUDA → to the inference control plane.

Developers won’t optimize for GPUs or LPUs.

They’ll optimize for NVIDIA’s inference APIs.

And NVIDIA will decide what silicon runs underneath.

That is the real lock-in.

7. Geopolitical and Antitrust Considerations

7.1 The deal structure is a regulatory strategy (but the economics are the story)

This is part of the broader trend: big tech pays large sums to take technology + talent while stopping short of a formal acquisition—an approach that has drawn scrutiny but has often survived.

For our purposes, that structure matters less than the operational outcome: Ross + key engineers move, the architecture moves, NVIDIA controls the roadmap.

7.2 Cerebras: the only remaining “pure play” in SRAM-first inference is now in a tighter box

Cerebras is Groq’s main rival in this HBM-less, SRAM-centric approach.

Cerebras’ wafer-scale WSE‑3 specs underline how serious SRAM-first designs can be.

Market implication: the competitive set compresses into:

Hyperscalers (internal chips + software)

NVIDIA (GPUs + now an absorbed alternative architecture)

A shrinking set of independents

8. The Hybrid AI Factory of 2026

The “One GPU to Rule Them All” era is ending—not because GPUs are weak, but because inference economics and supply-chain physics demand specialization.

The most defensible base case is not immediate dislocation. It’s a bifurcated architecture roadmap:

Training cortex: HBM-heavy, CoWoS-gated GPU factories (Blackwell → Rubin → beyond).

Inference organs: deterministic, SRAM-centric engines for decode-heavy, low-latency reasoning workflows.

Optical nervous system: a fabric roadmap that keeps scaling while power becomes the binding constraint (Part 2).

And the reason this “ages well” is simple: innovation cycles are shortening. Models iterate faster than hardware. Any architecture that can shift performance via compiler/runtime changes—without needing a brand-new silicon generation to keep up—wins more often in an era where the workload changes every quarter.

Actionable Insertions: The Signals to Watch (falsifiable)

You want signals that clearly validate (or falsify) the “Option 3 integration” thesis. Here are two clean ones:

Signal #1 — The “Jetson Pivot”

Watch for NVIDIA to re-brand or refresh its Jetson/edge/robotics line with Groq-derived IP first.

Why it’s the safest integration point:

Edge and robotics customers already accept heterogeneity, power constraints, and specialized acceleration. It’s the lowest-risk place to ship “non-GPU silicon” without spooking core datacenter GPU buyers.

What would count as confirmation:

A Jetson-class platform where NVIDIA explicitly markets deterministic token generation / low jitter inference as a core feature, and/or a Jetson module that contains a new inference accelerator block that looks architecturally Groq-like (compiler-scheduled, SRAM-centric).

Signal #2 — The “Speculative Decoding” Hybrid Card

Watch for a dual-slot card (or tightly coupled server tray) that pairs:

a GPU optimized for prefill/context (huge memory footprint)

with a Groq-like engine optimized for decode/generation (huge speed + determinism)

Why this is the holy grail:

The GPU holds the massive model and handles the compute-heavy prefill, while the deterministic engine drafts tokens quickly (and handles the latency-critical generation loop).

Why it’s plausible now:

NVIDIA is already openly treating inference as two phases (prefill vs decode) and discussing disaggregated serving as a throughput win; Rubin CPX being positioned for context/prefill is the roadmap breadcrumb.

What would count as confirmation:

Any NVIDIA product announcement that explicitly pairs “context chips” with “decode chips” in one SKU or one standard rack design—especially if decode silicon is not just “more GPU,” but a different architecture.

In the next section, we move past architecture and strategy and into the physical reality of scaling inference. We break down Groq’s deployment model at the level that actually matters for investors and operators: the bill of materials, the manufacturing lanes, the geopolitical hedge, and the new bottlenecks that emerge once you route around HBM and CoWoS. This is where the narrative shifts from “faster inference” to industrial procurement, brownfield data-center unlocks, cabling density, and who gets paid as inference capacity scales in the real world.

Part 9 — Supply Chain: NVIDIA’s Second Factory Door

(Why Groq turns inference into an industrial procurement problem)

9.1 The Product Isn’t a Chip. It’s an Orderable Rack.

The fastest way to misunderstand Groq is to argue about TOPS, latency charts, or benchmark deltas.

The correct way to understand Groq—and why NVIDIA effectively acquired it—is to look at what can be ordered, assembled, shipped, and deployed at scale.

Groq’s unit of deployment is not an exotic supercomputer. It is a standard server platform:

A 4U server chassis

8 accelerator cards

Conventional CPUs

Conventional DDR memory

Conventional NVMe storage

Conventional power supplies

A very unconventional amount of cabling